Inspired

INSPIRED

How to create tech products customers love

By Marty Cagan

One Quote

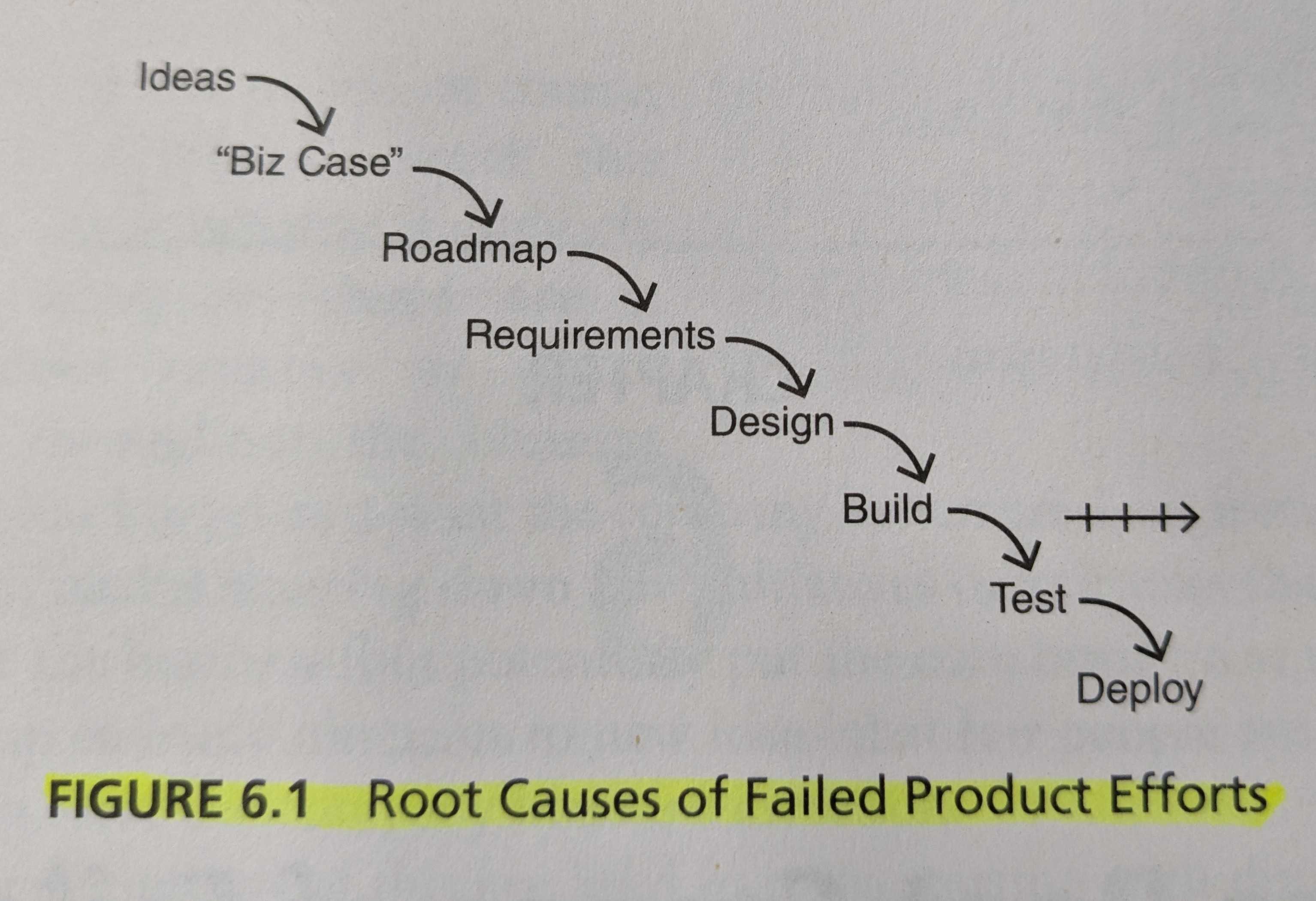

Let's start by exploring the root causes of why so many product efforts fail.

I see the same basic way of working at the vast majority of companies, of every size, in every corner of the globe, and I can't help but notice that this is not close to how the best companies actually work.

Let me warn you that this discussion an be a little depressing, especially if it hits too close to home, so if that's the case, I'll ask you to hang in there with me.

Figure 6.1 describes the process that most companies still use to create products. I'll try not to editorialize yet - let me first just describe the process:

As you can see everything starts with ideas. In most companies, they're coming from inside (executives or key stakeholders or business owners) or outside (current or prospective customers). Wherever the ideas originate, there are always a whole bunch of things that different parts of the business need us to do.

Now, most companies want to prioritize those ideas into a roadmap, and they do this for two main reasons. First, they want us to work on the most important things first, and second, they want to be able to predict when things will be ready.

To accomplish this, there is usually some form of quarterly or annual planning session in which the leaders consider the ideas and negotiate a product roadmap. But in order to prioritize, they first need some form of a business case for each item.

Some companies do formal business cases, and some are informal, but either way it boils down to the need to know two things about each idea: (1) How much money or value will it make? and (2) How much money or time will it cost? This information is then used to come up with the roadmap, usually for the next quarter, but sometimes as much as a year out.

At this point, the product and technology organization has its marching orders, and they typically work the items from the highest priority on down.

Once an idea makes it to the top of the list, the first thing that's done if for a product manager to talk to the stakeholders to flesh out the idea and to come up with a set of "requirements."

These requirements might be user stories, or they might be more like some form of a functional specification. Their purpose is to communicate with the designers and engineers what needs to be built.

Once the requirements are gathered up, the user experience design team (assuming the company has such a team), is asked to provide the interaction design, the visual design, and, in cases of physical devices, the industrial design.

Finally, the requirements and design specs make it to engineers. This is usually where Agile finally enters the picture.

Anyway, the engineers will typically break up the work into a set of iterations - called "sprints" in the Scrum process. So maybe it takes one to three sprints to build out the idea.

Hopefully the QA testing is part of those sprints, but if not, the QA team will follow this up with some testing to make sure the new idea works as advertised and doesn't introduce other problems (known as regressions).

Once we get the green light from QA, the new idea is finally deployed to actual customers.

[emphasis mine] In the majority of companies that I first meet, large and small, this is essentially how they work, and have worked, for many years. Yet these same companies consistently complain about the lack of innovation and the very long time it takes to make it from idea to customers' hands.

Okay, so that may be what most teams do, but why is that necessarily the reason for so many problems? Let's connect the dots now, so we can clearly see why this very common way of working is responsible for most failed product efforts.

In the list that follows, I'm going to share what I consider to be the top-10 biggest problems with this way of working. Keep in mind that all 10 of these problems are very serious issues, any one of which could derail a team. But many companies have more than one or even all of these problems.

phew. So all the companies he's seen work that way, and every company I've been part of has always worked that way too. I'll list the 10 problems concisely - check out the book for full detail.

1. This model leads to sales driven specials and stakeholder driven products, leading to lack of team empowerment.

2. Prioritization is a joke, because early on the amount of money you'll make and how much it's going to cost are shots in the dark guesses.

3. Ideas are locked in during quarterly sessions, but at least 50% of them are not going to work.

4. Product management isn't being utilized properly.

5. Design is engaged too late, resulting on "lipstick on the pig".

6. Engineers, who are the best source of innovation, are not even invited to the party.

7. It's only Agile in the final 20%.

8. Project-centric funding, staffing - resulting in emphasis on output rather than outcome.

9. Customer validation happens way too late.

10. Opportunity cost of all this wasted time and money.

It's All About the Product Team

This is probably the most important concept in this entire book:

It's all about the product team.

You'll hear me say this many different ways throughout the chapters to follow, but so much of what we do in a strong product organization is to optimize for the effectiveness of product teams.

In this book, they describe the two main activities undertaken by a product team which are (1) discovery and (2) delivery. Discovery is when you figure out what you should deliver. You want to make sure you deliver something that customers will want and pay for, and that is viable and profitable to the company. Discovery is intended to happen quickly, checking with inexpensive tactics to see if the idea is worth pursuing. Discovery must take an order of magnitude less money and time than actual product. You can quickly get customer feedback before actually sending an engineering team after it (complete with QA, documentation, pricing, and all the proper product things). Once we have narrowed down on what we should deliver, we switch to delivery mode and do all the proper product things.

The product team should:

- "feel real ownership for a product or at least a substantial piece of a larger product."

- Be missionaries, not mercenaries.

- Comprise of a product manager, a product designer, and 2-12 engineers. Optionally: a product marketer, test and automation engineer, user researcher, data analyst, and/or delivery manager.

- Be given clear objectives, and empowered to figure out the best way to meet those.

- Flat structure (no people managers). Product manager is not the boss of anyone on the product team.

- Be highly skilled.

- Be co-located.

- Be stable together (try hard to keep them together).

- Be given a significant degree of autonomy.

Product Manager

The product manager needs deep knowledge of the customer, deep knowledge of the data, deep knowledge of your business, and deep knowledge of the industry & market. They should be smart, creative and persistent. Learn quickly, be intellectually curious, think outside the box, and comfortable with discomfort. Honestly they probably need to be somebody who is willing to work a lot more than 40h per week. They need to be something like the CEO of a product. True leadership is important. In product companies, it is critical that the product manager also be the product owner.

Product Designer

The product designer understands the user experience and knows that this experience is critical. They think about the customer journey over time. They create a lot of prototypes. They are constantly testing their ideas with real users and customers. They are experts at interaction and visual design. For physical products, they need to know industrial design. "In strong teams today, the design informs the functionality at least as much as the functionality drives the design. This is a hugely important concept. For this to happen, we need to make design a first-class member of the product team, sitting side by side with the product manager, and not a supporting service.

Engineers

Engineers deliver the products. In addition they are consulted on discovery work. Sometimes the best ideas come from the engineers. The engineers will also help provide feasibility advice on your ideas. "You want to give your engineers as much latitude as possible in coming up with the best solution. Remember, they are the ones who will be called in the middle of the night to fix issues if they arise."

Leadership in Product

"The primary job of leadership in any technology organization is to recruit, to develop, and to retain strong talent. However, in a product company, the role goes beyond people development and into what we call holistic view of product.

There are 3 leaders the author suggests - head of product, head of design, and head of technology. These line up with the product teams which need product managers, designers, and engineers.

Head of Product

Competent in team development, product vision, execution, and product culture. You need a strong team, which means recruiting, training, and coaching. It means proven ability to develop others. If the CEO is a visionary, you need strong execution. If the CEO is not a visionary, the head of product needs to be. Either way the head of product has to complement the CEO. The head of product has to inspire and motivate their people to be all moving in the same direction. They need to instill a great product culture, meaning commitment to rapid prototyping and learning, and understanding the need to make mistakes on the path to learning. They should have experience in the company's industry or domain.

Head of Technology

This could be VP engineering or CTO. They need good organization, leadership to inform M&A activity, and STRONG delivery. They are responsible for orchestrating the architecture of the products company-wide. They lead the engineers, and serve as company spokesperson for all the engineers.

Product Vision

These are the 10 key principles for coming up with an effective product vision.

- Start with why. This is coincidentally the name of a great book on the value of product vision by Simon Sinek. The central notion here is to use the product vision to articulate your purpose. Everything follows from that.

- Fall in love with the problem, not with the solution. I hope you've heard this before, as it's been said many times, in many ways, by many people. But it's very true and something a great many product people struggle with.

- Don't be afraid to think big with vision. Too often I see product visions that are not nearly ambitious enough, the kind of thing we can pull off in six months to a year or so, and not substantial enough to inspire anyone.

- Don't be afraid to disrupt yourselves because, if you don't, someone else will. So many companies focus on their efforts on protecting what they have rather than constantly creating new value for their customers.

- The product vision needs to inspire. Remember that we need product teams of missionaries, not mercenaries. More than anything else, it is the product vision that will inspire missionary-like passion in the organization. Create something you can get excited about. You can make any product vision meaningful if you focus on how you genuinely help your users and customers.

- Determine and embrace relevant and meaningful trends. Too many companies ignore important trends for far too long. It is not very hard to identify the important trends. What's hard is to help the organization understand how those trends can be leveraged by your products to solve customer problems in new and better ways.

- Skate to where the puck is heading, not to where it was. An important element to product vision is identifying the things that are changing - as well as the things that likely won't be changing - in the time frame of the product vision. Some product visions are wildly optimistic and unrealistic about how fast things will change, and others are far too conservative. This is usually the most difficult aspect of a good product vision.

- Be stubborn on vision but flexible on the details. This Jeff Bezos line is vey important. So many teams give up on their product vision far too soon. This is usually called a vision pivot, but mostly it's a sign of a weak product organization. It is never easy, so prepare yourself for that. But, also be careful you don't get attached to details. It is very possible that you may have to adjust course to reach your desired destination. That's called discovery pivot, and there's nothing wrong with that.

- Realize that any product vision is a leap of faith. If you could truly validate a vision, then your vision probably isn't ambitious enough. It will take several years to know. So, make sure what you're working on is meaningful, and recruit people to the product teams who also feel passionate about this problem and then be willing to work for several years to realize the vision.

- Evangelize continuously and relentlessly. There is no such thing as over-communicating when it comes to explaining and selling the vision. Especially in larger organizations, there is simply no escaping the need for near-constant evangelization. You'll find that people in all corners of the company will at random times get nervous or scared about something they see or hear. Quickly reassure them before their fear infects others.

Risks

Marty spends a lot of time talking about understanding and mitigating risks such as: the risk nobody will want the feature, the risk users won't figure out how to use it, the risk we can't build it in a reasonable timeline with our team, and the risk that we can't make profit from it. Product discovery experiments are aimed at understanding these risks before deciding to deliver a feature. The most important thing is to establish a compelling value. We need to validate our ideas as fast and inexpensively as we can.

See the back 1/3rd of the book to see the author's treatment of validation techniques and key results. There are chapters on Discovery Framing Techniques, Discovery Planning Techniques, Discovery Ideation Techniques, Discovery Prototyping Techniques, Discovery Testing Techniques, Testing Feasibility, Testing Usability, Testing Value, Testing Business Viability, and Transformation Techniques. These techniques are useful for those engaged in product discovery.

Good Product Team / Bad Product Team

One of my favorite sections of the book is here. The author contrasts what good teams be/do/have vs what bad teams be/do/have. I'll share a few of my favorites.

- Good teams get their inspiration and product ideas from their vision and objectives, from observing customers' struggle, from analyzing the data customers generate from using their product, and from constantly seeking to apply new technology to solve real problems. Bad teams gather requirements from sales and customers.

- Good teams are constantly trying out new ideas to innovate, but doing so in ways that protect the revenue and protect the brand. Bad teams are still waiting for permission to run a test.

- Good teams engage directly with end users and customers every week, to better understand their customers, and see customer's response to their latest ideas. Bad teams think they are the customer.

- Good teams integrate and release continuously, knowing that a constant stream of smaller releases provides a much more stable solution for their customers. Bad teams test manually at the end of a painful integration phase and then release everything at once.

- Good teams celebrate when they achieve a significant impact to the business results. Bad teams celebrate when they finally release something.

OOF

There are a bunch more of these than what I highlighted. I really liked this super short chapter. Some of these hit a nerve. Time to up my game!